Treasures lie in the midst of housing developments, hidden within modern structures and under paved roads. As Kansas City grew, subdivisions to the south were platted by professional real estate developers and amateur speculators looking for a quick profit.

|

| 1877 plat map for the area shows the location of the Boone farm; current-day roads have been marked for reference. Click image for full view. |

But before there were subdivisions, hundreds of acres were held by various pioneer families. Sometimes those pioneers are remembered in the chosen name of a subdivision. Just south of 89th St. where I bought my first house and live today, Boone Hills was platted on land once owned by the descendants of the national folk hero, Daniel Boone.

There were Boones everywhere.

The first Boone to settle on this side of the state was Daniel Morgan Boone (1769-1839), the son of the famous frontiersman. He, along with twelve children, came to the area around 1825 when he was given a job as a farm instructor for the Kaw Indians.

In 1831, he patented acreage and built a log house at 63rd and Holmes. Known as "Morg" to friends, he sold part of his land to his nephew, Boone Hays shortly before his death.

On that land was what locals called the "Boone-Hays Graveyard," and when Morg died of cholera in 1839, he was buried there in an unmarked grave. In 1850, his wife was put to rest next to him.

With a family of this size... why? No one thought to mark the spot with a proper headstone??

The little two acre cemetery was used by people of the area to bury their loved ones for generations. Over the years, stones disappeared and next to nothing was left. In 1934, the Daughters of the American Revolution counted nine headstones, but it was known that dozens of others were buried there.

All stones were gone shortly after.

With the help of the Native Sons of Kansas City, fifteen acres of this farmland between Prospect and The Paseo (including the old cemetery) was donated to the city. In 2005, the Boone-Hays Cemetery was marked along with Morg and his wife's graves at 63rd and Euclid.

Morg's son, Daniel Morgan Boone, Jr. settled a bit further south of this spot.

Today, nestled in the middle of winding roads in Santa Fe Hills, stands the remnants of a pioneer homestead that has layers of history.

Simply stating the Boone family had an impact on Missouri is an understatement, and the image of Daniel Boone (1734-1829) as a folk hero with a coonskin cap is etched in our memory. This national legend was the grandfather of Daniel Morgan Boone (1809-1880) who came to Jackson County with his family in 1826 and settled later on land he purchased just south of current-day Waldo off the Santa Fe Trail (now Wornall Rd.).

Napoleon, James, and Edward Boone followed by patenting their own acreage south of 83rd St. Because of the influx of Boone family members, pioneers called the area “Boonetown.”

|

| Daniel Morgan Boone's surviving boys, taken after 1880 Standing: James (b. 1862), John (b. 1856) and Daniel IV (b. 1846); Sitting: Theodore (b. 1844), Napoleon (b. 1842), and Nathan (b. 1852) |

Sometimes, it feels like everyone in Missouri is related to Daniel Boone- and I mean that.

Daniel Morgan Boone and his wife, Mary Constance Philibert (1814-1904) had twelve children between 1833 and 1862. They raised all their children while living on their Jackson County farm.

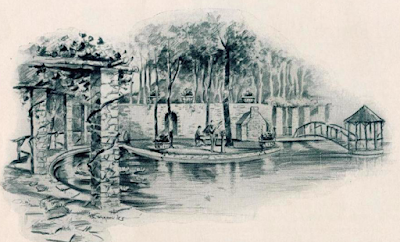

Around 1838, Daniel built a three-section clapboard house that developed into a two-story frame dwelling south of current-day 85th St. just east of the Santa Fe Trail. Over time, additions were added to the home as they further expanded. On the northeast corner of the property, the Boones used the creek passing through their land and added a pond.

The little Boone children recalled that during the Battle of Westport in October 1864, General Sterling Price’s Confederate troops fled south and were followed by Union soldiers. While hiding, they heard shots being fired near their home as the Confederate troops retreated to the town of New Santa Fe at current-day 122nd and State Line.

A one-room country school at the corner near current day Sweeney Blvd. and Maiden Lane was built in 1868 on land purchased from the Boones and became known as Boone School. In 1929, a four-room brick school at 89th and Wornall replaced earlier structures and was named Boone Elementary. It stands today.

The little Boone children recalled that during the Battle of Westport in October 1864, General Sterling Price’s Confederate troops fled south and were followed by Union soldiers. While hiding, they heard shots being fired near their home as the Confederate troops retreated to the town of New Santa Fe at current-day 122nd and State Line.

|

| Daniel Morgan Boone's surviving daughters & wife, taken after 1880. L-R: Sarah (b. 1854), Mary Frances (b. 1838), Mary Constance Philibert-Boone (wife; b. 1812), & Cassandra (b. 1849). |

After Daniel Morgan Boone’s death in 1880, his youngest son, Nathan (1852-1926) maintained the old homestead and continued farming the land. As he advanced in age, he opted to sell off much of his land. Nathan Boone didn’t marry until 1901 and had no children of his own. He stayed nearby at 85th and McGee where he lived out the rest of his life. The original Boone homestead passed along to one of Kansas City’s most prominent citizens who was looking for a quiet country life just outside the city.

Cue the rich newspaper man of notoriety!

|

| William Rockhill Nelson (1841-1915) Courtesy Missouri Valley Special Collections, KCPL. |

William Rockhill Nelson (1841-1915) is best known in Kansas City as a real estate developer and owner of the Kansas City Star. His primary residence, Oak Hall, was donated after his death and was torn down to make way for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Nelson always held an interest in livestock, and it was his hope to raise cattle on a large farm. In the 1880s, Nelson purchased the old Boone farm and hundreds of acres surrounding it and quickly made upgrades to the simple home.

Adjoining the original house, he built a large two-story lodge with a wide front porch overlooking Indian Creek. He often would take his friends from the city out to his lodge and entertain them.

Although his new residence and acreage was convenient to his primary residence at Oak Hall, he found he didn’t have enough acreage for his cattle. In 1901, he sold the property to the LaForce family.

In 1912, Nelson purchased his perfect farm (over 1,700 acres) just south of Grain Valley, Mo. and called it “Sni-a-Bar Farms” after the creek that ran nearby. There, he was able to raise shorthorn cattle and experiment with new breeding techniques until his death in 1915. In his will, he allowed for the breeding operations to continue for thirty years after his death.

On a side note, the City of Grain Valley has now purchased part of old Sni-a-Bar Farms with the hopes of saving the old farmhouse and using the land for a municipal office complex.

The LaForce family kept the land south of 85th purchased from Nelson until 1919 when it was sold to a self-made millionaire with a mission. Emory J. Sweeney picked up 180 acres for $205,000.

This story wouldn’t be the same without the influence of this incredible man.

|

| Emory J. Sweeney Image courtesy of Kansas City Public Library |

Born in 1883, Emory J. Sweeney came to Kansas City from Chicago at the age of seven with his parents. His father worked in the stockyards, and E.J. Sweeney followed at first in his father’s footsteps. Living in Kansas City, he attended Catholic grade school and fell in love with one of the neighborhood girls, Mary Smith. After one year of high school, he started buying and selling cattle.

Before he asked for his childhood sweetheart’s hand in marriage, Emory purchased a small four-room frame house in Kansas City, Ks. and worked on weekends to fix it up as best he could. Every week, he saved as much money as he could and purchased a piece of furniture that was stored in his soon-to-be father-in-law’s attic. In 1905, he married his sweetheart, Mary and started a family while continuing to trade in the cattle business. Unfortunately, he lost everything and had to start over.

Looking for a new business venture, Sweeney headed to the library with the hopes of checking out a few books about the chicken industry. The chicken industry, he figured, wasn’t as risky as cattle. While in the library, a book about automobiles caught his attention. He thumbed through the pages that detailed the mechanics of vehicles. He later told the Kansas City Star, “I took this book home instead of the chicken book, and read it and decided to be an automobile man.”

He picked up a job as a mechanic and earned $25 a week fixing automobiles. Before long, Sweeney was an expert mechanic and began training others. The growing automobile industry needed well-trained mechanics, and E.J. Sweeney came up with an idea: he could hands-on train men on how to fix vehicles.

In 1908, he founded Sweeney Auto and Tractor School, one of the first vocational schools in the nation. He advertised far and wide and became nationally known. In a short time, he had thousands of students coming to Kansas City to be trained. During WWI, the government put 5,400 men into his school for instruction and was able to use this financial windfall to expand his operations.

In 1917, Sweeney built a ten-story building across from Union Station for the school. The building included rooms for students to live in and even had a pool and a movie theater. The building still stands today.

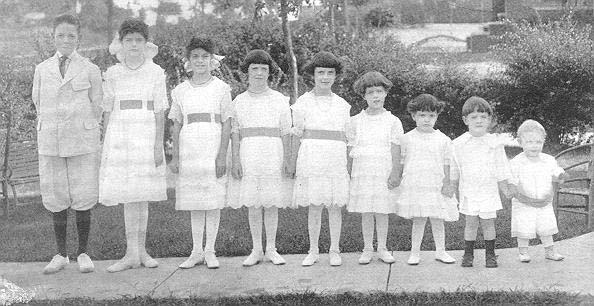

As his professional career was making him a millionaire, his personal life took an unfortunate turn when his wife, Mary- the mother of his nine children- unexpectedly passed away. After her death, he married a 20-year-old woman named Virginia Cassuth in 1918 and had one more child.

The 1918 flu pandemic gravely impacted Sweeney School (to read more about the 1918 flu in Kansas City, click here!). When the second wave hit in January 1919, 2,700 students were enrolled. Within three days, 1,100 of them were sick. Sweeney felt personally responsible for these men, so he borrowed money so he could pay their hospital bills. He told the Kansas City Star, “I took care of the sick boys, though I was paid only to teach them. Influenza became the country’s problem, but I made the boys my own problem.”

|

| The mansion at 5921 Ward Parkway built by Emory Sweeney for his new wife and children. |

His school was so popular that he decided to add an aviation school in 1919. In that same year, Sweeney built a sprawling 33-room mansion at 5921 Ward Parkway. The nine-bedroom home was built to be kid-friendly.

Sweeney and his new wife, Virginia along with several servants and his first wife’s mother moved into the massive property. He had bought an additional lot next door to the property on Ward Parkway for $50,000, enlarging the property to five acres; he had plans to build a personal art museum on the land. He did begin collecting art, and Sweeney served on the Kansas City Art Institute’s Board of Directors.

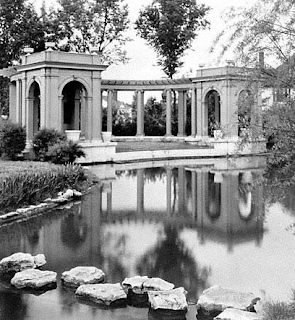

The incredible property featured a large fountain designed in 1922 by Jorgen E. Dreyer that was meant to not only be beautiful but act also as a swimming pool for his children.

This fountain and water feature sure was fancier than your average backyard pool.

|

| The fountain on the Sweeney property on Ward Parkway served also as a pool for his children. Photo courtesy of the Sweeney family. |

I could adapt to this lifestyle.

This “red-cheeked, jovial Irishman” told the Kansas City Star, "I've been lucky in my two wives and ten children. It was pure good luck that I got two such wonderful wives. The first one helped me make my fortune, inspired me, advised me. After she died, the second wife stepped in and raised the nine children of my first wife and gave me a tenth child, and made me a home that is a heaven on earth.”

Life had been good for self-starting Mr. Sweeney.

In 1922, WHB Radio was founded inside Sweeney’s school with financial help from Sweeney himself. As Sweeney’s financial success seemed inevitable, he continued to invest in projects that interested him. It is said that he ran speakers into public parks so that the nightly radio show could be played as people took their nightly strolls.

With everything working out so perfectly for Emory, it’s really no surprise that he decided to take more risks.

|

| A portrait of Virginia Sweeney was commissioned by her husband and featured in the newspaper in 1920. |

In 1919, he purchased 180 acres outside the city limits that held the original Boone farmhouse and an impressive addition by William Rockhill Nelson. The land bordered 85th St. on the north, 89th St. on the south, Wornall Rd. on the west, and Holmes on the east. The Dodson streetcar line reached the edge of the property.

His plan was to use the land for his aviation school- and those plans were vast. A $1.5 million dollar idea to build a self-sufficient school for his boys was the original hope.

The Kansas City Star reported that the new Sweeney School would “embrace mechanical and agricultural courses ranging from aviation to poultry raising.”

Apparently he went back to the library and got that chicken book.

This new school was supposed to house 2,500 students. 65 acres of the land would be set aside for an aviation field. He hired architects to design two-story structures covered with stucco and topped with tiled roofs to work as dormitories and classrooms.

The old Boone home that was enlarged by Nelson was to become a clubhouse and a library for students. His plan was to move the entire school operation out south by 1920 and repurpose his building across from Union Station into a 550 room hotel called “The Sweeney Hotel” – set to be the largest hotel in the entire city.

Why this didn’t happen is still a mystery. He chose to open his aviation school in Kansas City, Ks. You may know of the old site, as it later became Fairfax Airport.

Sweeney thought of another idea for use of his land at 85th and Wornall.

|

| The cover of the 32-page booklet Sweeney printed as promotional material for his subdivision. The sketches following all come from this booklet. Courtesy Kansas City Public Library |

He wanted to build “a small city” in the middle of the country- a new community built “for the man of moderate means- the man who wisely lives within his earning power- and to give to such economists an opportunity to have a real home.”

For whatever the reason, Sweeney saw opportunity when he looked harder at the investment he had made. In the center of this was a sturdy farmhouse, built originally by Boone and expanded by Nelson. For the first few years, Sweeney used the property as a place to take his second wife, Virginia and his ten children. Apparently, his mansion at 59th and Ward Parkway wasn’t “removed” enough from the bustle of Kansas City.

The 180 acres of land acquired could have stayed a farm, but Sweeney had envisioned something greater for the property. Although father to the north and to the east, subdivisions were surfacing on the outskirts of the city. And, a plus for homebuyers was that subdivisions south also didn’t have city taxes attached to the purchase.

With a beautiful home in the center of his land, Emory J. Sweeney had an idea as to how to profit.

Sweeney was about to enter the residential real estate business.

In 1923, E.J. Sweeney announced his impressive plans for a new subdivision he coined “Indian Village.” He chose the name “because this district will be populated by real Americans.” Just to the east of Sweeney’s new subdivision was Ivanhoe Country Club which had been organized in 1921. The private par-three course bordered the eastern side of Sweeney’s land and had a steady stream of golfers coming in from the city.

Hoping to “make a beautiful home a possibility for the average wage earner,” Sweeney enlisted renowned landscape architects Hare & Hare (who had designed part of The Paseo and the grounds of his home on Ward Parkway) to design the winding streets. 550 homes were carefully planned on streets paying homage to Native American history and folklore.

|

| The Dutch Mill on the property was one of the first things seen when entering at the main entrance at 85th and Wornall. It served as the real estate office. |

Pocahontas, Minnehaha, and Hiawatha are just some of the names chosen for Indian Village. Other streets such as Daniel Boone Rd. and Sweeney Blvd. were named for the original owner of the land and its developer. Virginia Lane was named after Sweeney’s second wife. Street signs were displayed on painted ceramic totem poles imported from Mexico.

I can’t make this stuff up!

This wasn’t your typical subdivision; it was built to be a thriving, self-sufficient community in the country. At the main entrance for “motor cars” at 85th and Wornall, Sweeney built a large Dutch mill that housed the real estate office after you entered the main gates. The choice of a Dutch mill may seem strange, but Sweeney insisted it made sense because the Dutch first established trading posts with Native Americans.

He even commissioned 68 street lamps to be on top of terra cotta totem poles that towered 18 feet high. At the entrance, a one-hundred foot “chime tower” with tubular chimes was placed to sound every fifteen minutes to alert residents of Indian Village of the time.

|

| 1940 tax photo shows the property after it was converted back as a single-family home. Image courtesy State Historical Society of Missouri. |

The old farmhouse built by Boone and enlarged by Nelson was to be the subdivision’s exclusive clubhouse. A peace pipe was hung above the mantel and hickory furniture was accompanied by Navajo rugs on the wood floors. A restaurant and even a daycare would be offered in the clubhouse for residents of Indian Village. The dining room- a part of the original Boone home- could be rented out to residents who wanted to host large parties.

Athletic amenities, including a football field, baseball diamond and running track would be available to Indian Village residents directly behind Boone School. Just to the east of the clubhouse, Sweeney built a fire station and a playground. The grounds already included an old barn, so Sweeney repurposed it to be the Town Hall.

|

| Sweeney ran hundreds of ads in the newspaper with hopes of enticing potential buyers with live music performed by musicians featured on WHB. This ad appeared in 1923 in the Kansas City Star. |

Near the Dodson streetcar line on the northeast corner of the property and close to what was then called Ivanhoe Country Club was a lake dug and filled by the Boone family. It was to be concreted and used as a swimming pool along with an “open air theatre.” Electric lights for “color effects” would be installed on the stage so that plays and WHB concerts were possible.

Advertisements printed in the paper urged homebuyers, “Be a good Indian and give your children a chance.” It was clear that Sweeney had envisioned a paradise inside Indian Village.

The first house for sale was built across the street from the country club (the old Boone-Nelson home) at 8734 Virginia Lane and was called “the Love Nest.” It was Spanish mission in style, a design quite new to the area and still, to this day, a bit out of place in the neighborhood. It was said that at the time, the “exterior stucco” was “in the cream, blue and orange coloring of the hacienda.” In front of the Love Nest and for a span of several homes, an ornate stone wall was built to give additional character to the budding neighborhood. Today, the remnants of this wall can be seen while traveling the winding streets of Virginia Lane.

|

| The "Love Nest" at 8734 Virginia Lane was the first home built in the subdivision. Courtesy Kansas City Public Library. |

A “demonstration house” furnished by the Jones Store was on the market for $6,000. Sweeney’s marketing was top-notch for his new neighborhood; he even had advertisements following the fictitious “Jack and Mary Jackson” as they went on their journey to find the perfect home. The actors chosen were Jones Store employees who worked with the developer to record short films as they pretended to find their dream home and establish themselves in Indian Village.

|

| The "demonstration home" that staged the factitious Jackson family featured in advertisements. The home sits at 8525 Hiawatha Road and has been added onto many times since it was built in 1923. |

The recorded films were advertised in the newspaper and everyone was invited nightly to the clubhouse at 7:30 to view “Jack and Mary” on their journey to the perfect Americana lifestyle. The film was shown as the Sweeney Radio Orchestra from WHB played live music as a soundtrack.

Lots were sold from $1800 to $4000, and Sweeney sweetened the pot by offering zero-interest loans for ten years to homebuyers.

His advertisements were so frequent that E.J. Sweeney even published a “census of Indian Village” in 1923 that proclaimed there were 374 married couples, two “eligible bachelors,” seven women (also “eligible”), and four widows.

The extensiveness of advertising was a big seller in Indian Village. E.J. Sweeney offered a free 32-page booklet to be sent to potential homeowners to sell Kansas Citians on the beauty of Indian Village. In truth, Sweeney went with what he knew; he had built his school with creative advertising throughout the nation. His gamble on Indian Village was gauged on his vision- he had to ensure it worked.

Sweeney proposed cutting off his winding roads in Indian Village from traffic to further entice the middle-class families to settle into his little subdivision. Anyone entering Indian Village to visit would be given a pass.

By the end of the 1920s, Sweeney had sold an impressive amount of the lots; however, not many people had built houses on the land. . .

And a financial mess what on its way.

Troubles began for Sweeney in 1928 when he was upside down in his various business interests. He opted to sell his 33-room home on Ward Parkway to lumberman Harry Dierks, and Sweeney “downgraded” to the Dierks 15-room home at 3727 Forest.

In March 1929 on the eve of the Depression, foreclosure proceedings on the south 99 acres of Indian Village had started due to default interest payments. Sweeney said the land was worth one million- but he owed $165,000.

|

| Virginia Cassuck Sweeney, namesake of Virginia Lane. |

“Big, aggressive, red-haired and robust,” E.J. Sweeney wasn’t about to go down without a fight. The government took away his radio license and were threatening to condemn his ten-story school building across from Union Station- a building he owned outright. Even though he had to liquidate his assets, Sweeney told the Kansas City Star, “I want you to tell the people who bought home sites from me in Indian Village that they won’t lose a dollar.”

Emory J. Sweeney was a self-made man whose willingness to take a risk worked – some of the time. Sweeney Automotive and Tractor School had brought thousands of young men from across the nation to the city, and the lack of the city’s help to continue its success was a thorn in Sweeney’s side.

Sweeney told Mayor Cowgill that there were two types of people who lived in Kansas City- those who lived off the city and those that made the city.

The city had been after Sweeney for his property across from Union Station because it had hindered their plans to build a municipal center between the station and the newly-built Liberty Memorial.

Due to so much financial loss, Sweeney was forced to sell Indian Village to an investment company financed by W.T. Kemper. By 1932, Sweeney was bankrupt and had personal assets of $775. He moved to Wichita to operate a branch of his automotive school and retired in 1951.

|

| A 1938 advertisement in the Kansas City Star notes the name change to Santa Fe Hills. |

The new development company had to simplify Sweeney’s lofty plans for Indian Village. In 1935, the development announced that the “club format” of Indian Village had ended -including private roads. There would be no private entries, exits or buildings within the subdivision.

By 1938, the original vision of Sweeney’s faded further when the totem poles, the windmill, and the stone pillars were removed. The original lake, playground, and athletic fields were eliminated and made into lots to be sold. The new developers scrapped the name “Indian Village” and renamed the community “Santa Fe Hills” as homage to the old Santa Fe Trail that crossed nearby. Ivanhoe Country Club followed suit in 1945 and renamed their 56-acre golf course “Santa Fe Country Club.” The Kansas City Star reported, “The original developer is given credit for an attractive street layout. Trees have matured in the passing years to add their share of natural beauty.”

Even though the subdivision lost its original name, the street names within the community stayed intact.

The old clubhouse, the site of the Boone farmhouse and Nelson’s summer retreat, was rezoned to be sold as a private family home.

|

| The south side of the Boone-Nelson home at 26 Porte Cimi Pas today; the front side has a large fence around it. The only Boone structure that remains is the far right side of the home. |

In the early 1940s, homes, “some cooled by refrigeration,” were advertised and enticed families to “live out in the country.” The housing boom after World War II helped fill most of the subdivision’s lots and ranch-style bungalows were built. Even though the “club” lifestyle was rejected, the character of Sweeney's dream remained.

This unique subdivision’s history explains why there are so many different styles of homes with very few looking identical to their neighbor. Some were built in the 1920s, and many weren’t constructed until the 1950s.

The subdivision wasn’t annexed to Kansas City until 1958.

Emory J. Sweeney lost almost everything in 1930- including his second wife, Virginia. He remarried for a final time and moved to Wichita to continue his school there. In a final twist of fate, he left Wichita and opted to spend his final years as a resident of his old subdivision. He purchased the two-bedroom Spanish-style home he had coined “the Love Nest” years earlier at 8734 Virginia Lane – the very first house built in his master plan of suburbia living.

|

| Top: the 1940 tax photo shows the old barn that was made into the Town Hall when Indian Village was developed. Bottom: the same structure was later repurposed as a residence at 8702 Rainbow Ln. |

That means his third wife lived on Virginia Lane- a street named after his second wife - and he was apparently proud of his creation enough to return to it years later.

I had the pleasure of talking to his grandson, Emory “Jack” Sweeney III on the phone, and he recalled some of those prized memories that one cannot find in newspaper clippings, booklets and official records kept in courthouses. Jack would ride his bicycle from his home at 75th and Walnut in order to visit his grandfather.

. . . Back in the days where the only bounds you had were how fast you could peddle a bicycle or move your feet.

That “Spanish-style house” that was one of the bright, beautiful showcases of the subdivision was his home after he was forced to surrender his interest in Indian Village- yet he moved back to the neighborhood. Even his grandson is surprised he chose to go back to the place that cost him so much.

Emory Sweeney's final quiet years were spent surrounded by his large Irish Catholic family.

In 1953 at the age of 69, Emory passed away of complications from heart disease at his home in Santa Fe Hills. His occupation at his time of death was not listed as an “auto mechanic”. . . He is listed as being a retired real estate broker.

The town listed on his death certificate is Santa Fe Hills.

The Sweeney family owned the “Love Nest” in the subdivision until 1962.

The Daniel Boone-William Rockhill Nelson home-turned-clubhouse at 26 Porte Cimi Pas was used as a group home and was later sold. Today, part of the original Boone house has been removed from the structure and is a private residence.

|

| The lake at Santa Fe Hills Country Club. In the distance to the west, Santa Fe Hills subdivision can be seen. Photo taken in 1964 by Bob Bliss. |

The Town Hall Sweeney had converted from an old barn was repurposed as a single-family home and stands today at 8702 Rainbow Lane. Santa Fe Hills Country Club to the east of the subdivision was sold in 1967 and the land was used to build apartments that stand today. The pond that was part of the old golf course is still found behind the apartments.

Although Sweeney’s vision for an affordable, exclusive subdivision didn’t come to fruition, portions of his original plan can still be seen throughout the winding streets of Santa Fe Hills. Pre-Civil War history along the old Santa Fe Trail is a part of the charm of this established neighborhood that was settled by the Boone family, improved by Nelson, and was repurposed by entrepreneur E.J. Sweeney.

Traveling through Indian Village- or Santa Fe Hills- is a trip through thousands of architectural plans. There is no such thing as cookie-cutter homes in the subdivision- and this has to do with the strange yet interesting history that encapsulates its very existence.

If this ground could talk, it would have stories that include many layers of Kansas City history.

I would like to dedicate this story to the Sweeney family and my friends, Kent Dicus and Sam Davidson who called Santa Fe Hills their childhood homes.

I would like to dedicate this story to the Sweeney family and my friends, Kent Dicus and Sam Davidson who called Santa Fe Hills their childhood homes.

This story was originally published in the Martin City Telegraph in two parts and was expanded for this blog.

* * * * *

* 😁 Don't want to miss any of my writing? Search The New Santa Fe Trailer on Facebook and LIKE my page so you don't miss any of these fascinating stories!

* 😁 Don't want to miss any of my writing? Search The New Santa Fe Trailer on Facebook and LIKE my page so you don't miss any of these fascinating stories!

* *😀 Do you love Kansas City history and my writing? You have to check out my FREE podcast produced by Entercom Radio. Along with radio personality Bob Fescoe, we discuss the history of our city! It's completely free. Click HERE!