Spring 1912

He certainly was glad he brought his work boots in his automobile as he climbed the muddy hill to the north. His motor car couldn't even make the journey- roads did not yet exist on this undeveloped plot between bustling downtown and his subdivisions to the south. The marshland was an eyesore; it was dotted with shacks, shanties and a quarry that blasted at all hours of the day.

He knew he had to do something about it as he continued to convince the wealthy to call his beautiful houses home sweet home. He was a visionary- a man beyond his years who could look at this land and see something truly stunning for its future.

Adjusting his wire-rimmed glasses, J.C. Nichols took a handkerchief out of his jacket pocket and rubbed his nose. After taking a deep sigh, he put one hand on his hip and the other above his forehead to block the sun. An employee unfolded a map in front of him and pointed out the different parcels of land. It would be difficult to buy up this property, he reasoned. It would take years to track down all these names listed on the map in order to make his vision a reality.

Regardless of the challenge, Nichols knew it was important to the suburbs to continue his mission. As he stared to the south, he could see the continuation of roads from Westport and downtown into his new community- he wanted to create a shopping area that would serve his beloved Country Club District. Yes, it would take years. And yes, there would be naysayers that would scratch their heads in disapproval. He paid them no mind.

Jesse Clyde Nichols had a plan. He always did.

When out-of-town

visitors come to Kansas City, one of the first spots to see is the Country Club

Plaza. With its unique architecture, show stopping fountains, gorgeous

landscaping and holiday lights showcased on tv stations nationwide, the Plaza

is quintessentially Kansas City.

He certainly was glad he brought his work boots in his automobile as he climbed the muddy hill to the north. His motor car couldn't even make the journey- roads did not yet exist on this undeveloped plot between bustling downtown and his subdivisions to the south. The marshland was an eyesore; it was dotted with shacks, shanties and a quarry that blasted at all hours of the day.

He knew he had to do something about it as he continued to convince the wealthy to call his beautiful houses home sweet home. He was a visionary- a man beyond his years who could look at this land and see something truly stunning for its future.

Adjusting his wire-rimmed glasses, J.C. Nichols took a handkerchief out of his jacket pocket and rubbed his nose. After taking a deep sigh, he put one hand on his hip and the other above his forehead to block the sun. An employee unfolded a map in front of him and pointed out the different parcels of land. It would be difficult to buy up this property, he reasoned. It would take years to track down all these names listed on the map in order to make his vision a reality.

Regardless of the challenge, Nichols knew it was important to the suburbs to continue his mission. As he stared to the south, he could see the continuation of roads from Westport and downtown into his new community- he wanted to create a shopping area that would serve his beloved Country Club District. Yes, it would take years. And yes, there would be naysayers that would scratch their heads in disapproval. He paid them no mind.

Jesse Clyde Nichols had a plan. He always did.

* * * * * *

|

| Jesse Clyde (JC) Nichols' graduation photo from the University of Kansas |

The early history of

the Country Club Plaza embraces the growth of the city to the south and the

innovation of one brilliant man who saw past a swampland; he could envision the

future of the suburbs- the need for shopping nearby that catered to a new, growing

mobile society.

Jesse Clyde Nichols

(1880-1950), better known by his initials “J.C.,” made a name for himself as a suburban

planner who greatly influenced how our city grew to the south. In 1907, he began

development of what is known as the Country Club District, deriving its name

from nearby Kansas City Country Club (now Loose Park). What started as a

ten-acre piece of land far away from downtown, the area grew to fifty subdivisions

that shied away from the grid system of streets and embraced the natural

landscape with all its curves.

I could go on for days about J.C. Nichols and his contributions to Kansas City. And, don't worry- it will happen- very soon!

J.C. Nichols's objective was to "develop

whole residential neighborhoods that would attract an element of people who

desired a better way of life, a nicer place to live and would be willing to

work in order to keep it better." Skipping over Brush Creek and building

first to the south, Nichols knew he needed to ensure his developments offered

all the modern conveniences of the era in order to attract wealthy and influential

people to the area.

|

| Mill Creek Boulevard from 42nd St. facing north in 1911 shows how isolated the area would have been. Image courtesy of John Dawson |

Even when he gazed at the land that would become the Plaza, he knew how difficult it would be to track down all the people who owned small parcels that would become part of his plan. Many of these landowners had never even step foot in Kansas City, and it would take years to track them all down.

|

| Lyle Rock Company at 49th and Baltimore |

The company was a

constant complaint for neighbors who had purchased homes in the Country Club District.

Even though Lyle Rock Co. had established their quarries in 1907, those moving

south were unforgiving- the business was a constant problem. People living

around it called it a “war zone.” Explosions rocked people’s foundations- one

witness said a two-pound stone from a blast shattered his brand new front

porch. J.C. Nichols called it “unsightly in its condition.”

It took J.C. Nichols

nine years to buy up the land in the area, including Lyle Rock Co. In 1921,

Nichols spent one million dollars to acquire forty acres at the future site of

the Country Club Plaza. In total, 26 houses and stores in bad condition were

leveled to the ground.

|

| An illustration from the Kansas City Star of Lyle Rock Co. smoke barreled onto the newly-established JC Nichols neighborhoods. |

It certainly would

have been easy to plan another housing development, but Nichols was a man ahead

of his time. Although most Kansas Citian's didn’t own automobiles, he could see

that the car was the future. Accessibility, he reasoned, would spread retail

sales past Petticoat Lane and the stores downtown.

|

| Edward B. Delk's original design for the Plaza in 1922. Image courtesy of Robert and Brad Pearson. |

|

| Edward Delk (1885-1956). Courtesy of Oklahoma Wesleyan University |

The design, centered

around a diagonal, tree-lined thoroughfare called “the Alameda” (renamed Nichols

Rd. in the late 1940s). When construction began in Spring 1922, Nichols

commented, “It is essential the new district be not only attractive to the eye,

affording also a maximum of convenience, but that it be made commercially

profitable.” Despite J.C. Nichols’ ambition for his Country Club Plaza,

developers and business owners thought he was crazy. It was too far from downtown

and blocks away from the streetcar line- no one would go there, they contended.

Before the Plaza opened for business, people called it “Nichols’ folly.”

J.C. Nichols didn’t

listen to the naysayers. He simply stated that he believed his Plaza plan could

become the model of outlying business districts around the country.

He was right.

|

| Aerial view of the Plaza before development. Image courtesy of Robert and Brad Pearson |

In November 1922, the

first building, called the Suydam Building after its first tenant (an interior

decorating company) opened its doors at current-day 47th and J.C.

Nichols Parkway. The Marinello Beauty Shop opened up inside and offered Kansas

City’s first place to get the “permanent wave.” By the following year, the Plaza

featured an art and gift shop, baby shop, a drug store, a mechanic, a florist,

photographer and a millinery shop. At first, customers were scarce, so Nichols

asked merchants to park on the street to make the new business district look

busier than it was.

He touted the shopping

district as “The Country Club Plaza: Where shopping is a pleasure.” Within the

year, J.C. Nichols got his wish- people began to drive their motor cars to shop

on the Plaza and its first fountain featuring a boy and fish began shooting

water. This fountain was moved to 76th and The Paseo in 1968.

|

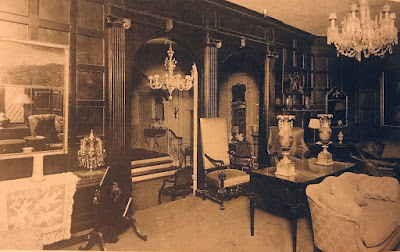

| Suydam Decorating Company in the Mill Creek (Suydam) Building in 1923. |

Shortly thereafter, Wolferman’s opened on

the Plaza and became the second grocery store in the development. The advertisements for Wolferman's showcase, surprisingly, how cleanliness was a cornerstone for their business. "It is a marvel of hygienic cleanliness and modern equipment from the spotless bakery with its white tiled walls and floor to the sausage kitchens, ice box and meat department." Elite

customers phoned in their orders and distinctive Wolferman’s trucks would

deliver groceries to customers’ doors. In

the same year, the Tower and Balcony Building were open for business.

|

| Wolferman's Grocery Store in the 1920s |

J.C. Nichols wanted

to encourage clean streets and upscale businesses and wouldn’t allow merchants

to load and unload goods in the streets- he designed loading docks in the back,

an innovation at the time. He would walk the streets at night and take

meticulous notes, scribbling down when fingerprints could be found on doors or

when a window display was quite impressive. A letter typed and delivered to

merchants the next day would warn or praise the merchants.

In December 1925,

merchants decided to decorate the pristine sidewalks with mini Christmas trees.

Likely in the holiday spirit, a J.C. Nichols employee who helped lease space

along the Plaza named Charles Pitrat stood at the Suydam building, wishing

merchants a Merry Christmas.

|

| J.C. Nichols with the Plaza Christmas lights in the 1920s. |

To be fair, there

were few witnesses and no grand flipping of the switch on Thanksgiving night.

It took a few more years for Christmas lights along the Plaza to become a

showcase. In October 1928, the Plaza Theater opened its doors at 207 W. 47th

St., seating 2500 and showcasing the tallest tower at the time at over twice

the height of any other at 72 feet.

The $750,000 construction

of the Plaza Theater building was a monumental occasion, and for the Christmas

season in 1928, the new building featured the first-ever outdoor strand of

continuous lights on 47th St.

Just one year later, the buildings were outlined in multiple colors and followed the architecture so significant to the Plaza. For every year since, minus 1973 when Nixon called for conservation of energy, the Plaza lights have been a staple of Kansas City’s rich history. It is said that the Plaza lights inspired companies to make stronger bulbs that were weatherproof, thus the creation of outdoor Christmas lights.

Just one year later, the buildings were outlined in multiple colors and followed the architecture so significant to the Plaza. For every year since, minus 1973 when Nixon called for conservation of energy, the Plaza lights have been a staple of Kansas City’s rich history. It is said that the Plaza lights inspired companies to make stronger bulbs that were weatherproof, thus the creation of outdoor Christmas lights.

|

| The Plaza Theater in 1932. Image courtesy Missouri Valley Special Collections, KCPL |

There was one flaw

in J.C. Nichols plans. He didn’t add parking for cars because he was under the

impression that apartment dwellers wouldn’t be able to afford them. He was

gravely mistaken. By 1930, 60 percent of the nation owned a car, and the number

post-Depression only grew higher. The ability to be mobile, as he had predicted

for his elite neighborhood clientele, had trickled down to the working class.

This mistake was something he deeply regretted.

This mistake was something he deeply regretted.

J.C. Nichols’ vision

for The Country Club Plaza solidified his Sunset Hills and Mission Hills

neighborhoods as the most desirable in Kansas City. In 1915, these communities

housed ten percent of the elite; by 1930, 59 percent of the most prominent families

called his neighborhoods home. Their popularity, no doubt, had much to do with

the gamble he took when developing the Plaza.

|

| The Plaza apartment buildings on the south side of Brush Creek replaced Lyle Rock Co. They also lacked parking. |

Jesse Clyde Nichols

said in 1922, “I realize, in the laying out of these plans, that it will take

many years of Kansas City’s growth to carry out our development. But I really

feel that this plan is no larger undertaking, nor more difficult to accomplish,

than the development of the Country Club District in the beginning.”

|

| The Plaza in the 1930s |

His plan, indeed, worked.

* * * * * *

The influence of J.C. Nichols on KC will be featured SOON! Please stay tuned!

* Please go to Facebook, search "The New Santa Fe Trailer," and LIKE my page so you don't miss my writing!

**If you like my writing, you would LOVE my free podcast with radio personality Bob Fescoe! Kansas City: 2 States, 1 Story is all about our history in KC. Please consider downloading the episodes so you can take a listen anytime-anywhere! Click here to see what we've been up to. It's FREE!

*** Recommended reading: The J.C. Nichols Chronicle by Robert and Brad Pearson

Images below are all courtesy of Missouri Valley Special Collections, KCPL.

|

| The Plaza lights today |