Nightfall had overcome the prairie the sweltering evening of

August 21st, 1863; few sounds echoed in the darkness in the middle of the night. They

had avoided the manhunt by taking high prairies and divides between Bull

Creek and the Marias des Cygnes River. They had turned into the timber, and in

the darkness, had escaped into the night. Quantrill and his men continued to

creep with solidarity southbound.

They needed to get back into safer territory. They needed to

cross into Missouri.

Senator James H. Lane, a notorious Jayhawker and Union

general, emerged after narrowly escaping the attack in Lawrence. Through the

burning cinders and ashes of the town of 2,000, Lane looked for reinforcements

in order to chase the murderers. Knowing very well that he was one of Quantrill’s

targets, the unpredictable senator rallied farmers to grab fresh horses and

follow the guerrillas. Lane had no

intention of letting Quantrill get away this time.

|

| The Lawrence Massacre, August 21st, 1863 |

Gen. Ewing did not have fate on his side. He was delayed at

the Kansas River at De Soto, Ks. because they couldn’t find boats to cross the

waters. Hours crept by as Ewing was left restless and exhausted. As he was

caught in wait on the river, Quantrill quietly continued on his route to safety.

|

| Sen. James H. Lane (1814-1866) |

Some were, in fact, captured and killed. But the big fish

was still out there.

The raiders, after killing close to 200 men and boys in what

would be coined the Lawrence Massacre, slipped somewhat silently into Missouri in Cass Co. and

closely watched at a fork of the Grand River as federal troops continued their

manhunt.

By daylight the next day, the famished guerrillas halted to take a quick meal in small prairie surrounded by trees. Before they

could feast, a warning came that troops were nearby.

There was no choice; Quantrill and his men had to proceed. A small skirmish with

troops ensued, yet, as always seemed to be true, Quantrill and most of his men fled

through the forest to fre

Gen. Ewing, dangerously affected by the delay in De Soto,

didn’t arrive to the Missouri border where Quantrill crossed until after dark on

the 22nd- hours and hours after Quantrill hopped into his familiar territory

where friends were aplenty.

Sen. Lane lost his search of Quantrill, yet his rage was not

adrift. He had plenty of time, fatigue the enemy, to fester over the intense

hatred he had for these guerrillas. Gen. Ewing and Sen. Lane met near the

place where Quantrill and his men were known to stop four miles east of the

Missouri-Kansas border. Lane, an incredible extemporaneous speaker, spat his

frustrations at Gen. Ewing and demanded something drastic be done.

If Ewing wasn’t going to do anything, Lane and his

Jayhawkers certainly would.

********************************************************************************************************

|

| William Quantrill (1837-1865) |

And if he’s right, this little log cabin would be a

significant rediscovered piece of Civil War history for the ages.

A man had recently bought 80 acres of land north of Freeman,

Mo. Before the new owner was to bulldoze the structures on it, he knew it was

best to contact the experts about what he believed was underneath the abandoned

house on the land.

A log cabin enthusiast, Peters was perfect for this new

project. He had already successfully saved three other cabins in Missouri, but

a cabin surviving the Border Wars and Civil War was an anomaly. As any good

historian would do, he dug deep into the records to learn more about the

history of the land and the family attached to it.

“Albert Sloan cleared the land and built this log cabin,”

Peters explained. From its construction, Peters believes the cabin to be built

in the late 1830s or early 1840s.

The first landowner was Alfred G. Sloan, born around 1805 in

Barron Co., Ky. He married his first wife, Elizabeth Standiford in Indiana, and

by the 1830s, Sloan and at least one of his brothers settled in what is now

Cass Co. (then called VanBuren Co.).

Accounts from the Sloan descendants are recorded in the

history of Cass Co. Family lore indicates that when Alfred rode into Pleasant

Hill on a black pony with his wife, he met a Native American. Alfred wished to

find land with plenty of water sources, and the old Indian led them to land

north of Freeman, Mo. where the South Grand River's forks spidered on

the land. In thanks, Alfred turned over his black pony to the old Indian.

He patented 240 acres of prime real estate in 1845. As with many early settlers of the

western portion of Missouri, it is likely that Alfred Sloan was a “squatter,”

meaning he had settled on the land well before he had purchased it from the

government. The 1840 census shows that Alfred had already moved to Cass. Co. earlier,

showing that the construction of the cabin was, in fact, by the late 1830s.

After all, a family of eight had to have a place to sleep.

Alfred’s brother-in-law, Hiram Boone Standiford, founder of

Stanton, Ks., was a member of the Territorial Legislature before Kansas was a

state. In E.W. Robinson’s History of

Miami County, he wrote of Standiford: “He was a leader to be trusted, a

friend warm and steadfast. . . In public life, he was an uncompromising

Free-state man. . . He had been an anti-slavery member of the Missouri

Legislature.”

|

| Alfred G. Sloan and Serepta White. Courtesy of the Sloan-Tribby descendants. |

This connection to the very beginnings of the fight for

abolishment of slavery is significant. Alfred G. Sloan seems to have sided with

his in-law’s family.

Earlier in 1845, the same year Alfred patented his acreage

in Cass Co., his wife passed away. He

then married Serepta White and had nine more children, bringing his offspring

total to 15. By this time, tensions in the area ran high due to frequent raids

by Kansas free staters and the Missouri bushwhackers.

The nearest town was Morristown, now erased from the

landscape and was one mile northwest of current-day Freeman, Mo. By the 1850s,

Morristown had a general store and later a flour mill.

The troops had no problem taking from the neighbors-

especially from secessionists that were allies of Quantrill and the

bushwhackers.

The town, by 1862, had been ransacked and only five

buildings stood. Nearby Harrisonville had been taken and occupied by the Union.

|

| Part of Plate 161 from the Military Atlas of the Civil War. The red star marks the location of Morristown. |

This type of tyranny on the border was all-too-common. Families,

such as the Sloan’s, stayed put for a time in hopes that the warfare would calm

down. The nearest town- what they had most likely considered their hometown-

had been nearly ruined.

|

| The house before the removal began. |

Don Peters’ excitement mounted as he kept uncovering

substantial evidence on this preserved piece of Missouri history. He surveyed

the site and began to gingerly tear away the more modern frame house. With

every board that was torn carefully away from the yellow paneling that covered

it, a perfectly in-tact log cabin emerged.

|

| Cabin hidden under that more modern structure begins to be revealed. Courtesy of Lonnie Peters |

“Whatever wood they had available is what they would have

used,” Don explained.

As he examined the structure, he noted some interesting

anomalies. “There were no bullet holes in it, and I could find no evidence of

fire damage,” Peters noted.

During this time in Missouri-Kansas Border War history, it

is quite uncommon to find a structure this old completely unharmed by warfare. Tom

Rafiner, historian and author of two books, Cinders

and Silence and Caught Between Three

Fires, explained, "A number of cabins that survived in the area during

the Civil War were used by Union companies as stations. The houses that did

survive outside of the Pleasant Hill or Harrisonville military posts were used

by counting parties or patrols sent out. They grabbed a hold of a cabin to

use."

|

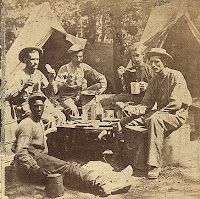

| Union soldiers cooking in camp. Courtesy of the Library of Congress |

Well, most cabins from this era didn’t have basements. When

Don neared the foundation of the old home, his eyes widened and a smile followed

as the base of the structure saw light for the first time in over a century. There

it was. A small, 10 to 11-foot cellar with a small opening- with walls almost

six inches thick.

There’s nothing like physical corroboration of paper records

found.

Oh, but those records had a lot more to show that this cabin

could possibly have served as a significant piece of Civil War history after

Alfred and his family fled to Miami Co.

|

| Capt. J.A. Pike |

This is no more than five miles northeast of Alfred Sloan’s

cabin and implies that Quantrill entered Missouri just west of where Cleveland,

Mo. is today.

Exhausted and famished, the bushwhackers then stopped to get

something to eat after dawn on August 22, 1863, less than 24 hours after

sacking Lawrence. In Quantrill and the

Border Wars by William E. Connelley, published in 1910, the author states, “The

main body of the guerillas was then four miles from the state line in Missouri,

at the head of a branch of the Grand River.”

When Don discovered this information, his heart raced at the possibilities. As the history books indicate, the federal troops were hot on their tails, thus they abandoned their resting point and disappeared into the brush.

When Don discovered this information, his heart raced at the possibilities. As the history books indicate, the federal troops were hot on their tails, thus they abandoned their resting point and disappeared into the brush.

“How many log cabins could have been close to this location?

They were few and far between, especially after the Border Wars and the

fighting during the Civil War,” Don declared.

To put this into perspective, only 1,312 people lived in all

of Dolan Township in Cass Co., Mo. in 1860. Many had fled at the outbreak of

war- including the Sloan family- so this number is likely high. Tensions

locally were further ignited by constant invasions of border ruffians.

Sen. Lane’s stewed in his fury as he crossed into Missouri.

He recognized that personally catching up to Quantrill’s raiders was out of the

cards, yet his hope remained that troops would be able to corner them in the

brush.

|

| Sen. James H. Lane |

As troops gathered behind Gen. Ewing, Sen. Lane and his

small group approached. In Quantrill and

the Border Wars, it reads, “General Ewing and Senator James H. Lane met at

the point where Quantrill had stopped first after crossing back into Missouri.”

This information certainly peaked Don Peters’ interest. When

he looked at the maps and compared the location of where Quantrill had stopped

and where the Sloan-Tribby cabin stood- perfectly unharmed- he wondered.

Further documentation in Forty-Six

Years in the Army by Maj. James M. Schofield shows that at this fiery meeting,

“General Ewing and General James H. Lane met at Morristown and spent the night

together.”

Dr. Jeremy Neely, professor of history at Missouri State

University and author of The Border Between Them: Violence and Reconciliation on the Kansas-Missouri Border stated, “After the Lawrence massacre, Lane and other furious

Kansans, many of whom blamed Ewing for failing to stop Quantrill's raid,

threatened a retaliatory raid across the state line. Ewing, meanwhile, had supported increasingly

forceful policies against the households whom he suspected of aiding

pro-Confederate guerrillas.”

|

| Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing, Jr. (1829-1896) |

Sen. Lane was famously known for his persuasive speeches and

outspokenness. Gen. Ewing, more cautious and reserved, had been stewing over

how to squash out the bushwhackers along the border. Sen. Lane, in this meeting

in a cabin near Morristown, insisted that if something was not done soon, he

would go to Washington and have him removed from his position.

In Connelley’s book, he described this meeting of Ewing and Lane. His

information came from Col. Elijah F. Rogers, a member of the Missouri militia

who had heard it from Lt. William Mowdry. He wrote, “Lane agreed to make no

complaint if Ewing would issue the order, which had been under consideration

for some time, depopulating portions of some of the border counties of

Missouri. Ewing agreed to do it, and they went to a cabin near-by.”

Let’s just consider that there weren’t subdivisions of

cabins in 1863. There were very few buildings left standing after the Border Wars

and during the Civil War. And as Don pointed out, this cabin was left with no

damage. And it’s near Morristown- within a mile. It’s not far from the branch

of the Grand River four miles from the state line.

In fact, when I drew a circle and analyzed the maps myself,

Don proved to be right. This cabin would meet the description perfectly. When

you further consider that Alfred Sloan’s brother-in-law was involved in the

Territorial Legislature and the cabin was unharmed, the preponderance of the

evidence shows that this is cabin could be where Ewing and Lane met.

|

| This map from 1877 showcases the cabin. It sat just over four miles east of the Kansas-Missouri border. |

I asked Tom Rafiner, one of the most well-known writers and

historians of the early history of Cass Co., about this possibility. "Don

makes a compelling case. Ewing and Lane's meeting place is definitely in that

area. There is a reasonable chance that this is the place."

The prospect of this perfectly in-tact log cabin being where

Ewing and Lane met has historians talking. Is there a smoking gun that could

prove or disprove this theory?

“How many log cabins could possibly have been standing at

this point? This cabin- the Sloan-Tribby cabin- was. That, we certainly know,”

Peters persisted.

The order in which Gen. Ewing and Sen. Lane discussed on the

22nd of August came to fruition when Ewing rode north to Kansas City

and sat down at the Pacific House Hotel. Three days later, he signed Gen. Order No.

11, one of the most controversial orders placed on civilians during the Civil War.

In part, the order states:

All persons living in Jackson, Cass, and Bates counties,

Missouri, and in that part of Vernon included in this district, except those

living within one mile of the limits of Independence, Hickman's Mills, Pleasant

Hill, and Harrisonville, and except those in that part of Kaw Township, Jackson

County, north of Brush Creek and west of Big Blue, are hereby ordered to remove

from their present places of residence within fifteen days from the date

hereof.

|

| George Caleb Bingham's "Order No. 11" painting, completed at his studio in Independence, Mo. in 1865-1870 |

After the order was enforced, the area became known as “The

Burnt District” due to the fact that it was a no-man’s land after the

evacuation. Houses were burned to the ground after they were looted for their

goods. There are very few surviving structures pre-Civil War in the Kansas City

metropolitan area due to Ewing’s decision to depopulate the area after the

Lawrence Massacre.

Lane kept to his word; he rode back into Kansas and defended

Gen. Ewing.

The resounding effects of Order No. 11 can be read in full by clicking here: Everything Ablaze on the Western Border: Ewing's Order No. 11.

|

| The Sloan-Tribby house in early 1900s. Courtesy of the Sloan-Tribby descendants |

For whatever the reason, Alfred and his wife decided to

return to Kansas where he died in Paola in 1893. His second wife, Serepta,

died in 1909 in Oregon. His daughter from his second marriage, Katie Tribby

(1860-1952), took over his beloved farmstead with her husband, Mark, where it

remained in the family for many years. Around 1900, the Tribby’s added a second

floor to the western addition. A wrap-around porch in the Victorian gingerbread

style completed this updated look and completely masked the plain log cabin.

|

| One of the carefully numbered logs |

Shane DeWald, Parks Director for Belton Parks jumped at the

chance to have the Sloan-Tribby cabin as a part of their facilities. “We took

it to the Park Board, and everyone rallied around it,” DeWald stated.

A few presentations are in the works to further raise money

and awareness of this incredible piece of Missouri history. Hopes are to have

the cabin up and ready for visitors by June 2018.

Today, the cabin sits protected in a warehouse, each board

carefully numbered and waiting for reconstruction at Belton’s Memorial Park.

|

| A 1900s croquet match outside the Sloan-Tribby house. Courtesy of the Sloan-Tribby descendants. |

They will need around $70,000 and donated materials in order

to restore this cabin. DeWald is working now to get the foundation underway at

Belton Memorial Park, where the cabin will be raised near the arboretum. The

Chamber of Commerce is working on fundraising efforts.

Historians still are waiting for the “smoking gun” in order

to definitively state whether this cabin is, in fact, where Ewing and Lane had

their meeting after the Lawrence Massacre.

"To be able to

definitively say it's the cabin where they met, we need to find a letter or

further documentation possibly mentioning the family that lived in the cabin

and its connection... Someone will have to devote time and effort to uncovering

more that may still be out there," historian Tom Rafiner stated.

Even if it’s “just” a

log cabin, it holds importance because it was one of the very few on the

western border that survived the Border Wars and the Civil War.

Don Peters is waiting for someone to prove him wrong about

his assumptions of the significance of this cabin. Don proclaimed with

excitement and a twinkle in his eye, “If this is what I think it is- and all my

research shows true -this cabin is the Appomattox of the West.”

|

| The plans at Belton Memorial Park includes featuring the Sloan-Tribby reconstructed cabin. Courtesy of Shane DeWald, Belton Parks and Recreation |

Maybe the evidence is in an attic, tucked away in a journal

of a Civil War soldier. Perhaps the piece to connect this cabin is still out

there to be found.

Belton

Parks and Recreation is looking for donations, including lighting/electrical,

stonework, cabin assembly, heavy equipment, walkway stones, landscaping, surveillance

cameras, fencing, roofing, windows, doors, and various other pieces to bring

this piece of history back to life. If you are or know someone who could help,

please contact Belton Parks at https://www.beltonparks.org or email Diane Euston (the writer) at thefamilygenies@gmail.com.

**Please consider LIKING my Facebook page as well! Search "The New Santa Fe Trailer" so you don't miss any of my writing from the blog and the Martin City Telegraph! :)

**Please consider LIKING my Facebook page as well! Search "The New Santa Fe Trailer" so you don't miss any of my writing from the blog and the Martin City Telegraph! :)

As a matter of coincidence, my small town in Colorado is currently reconstructing a hewn wood cabin with ties to historic events of the 1860's and 70's. In Beulah, Colorado, the Dotson Cabin has been painstakingly disassembled and relocated to property adjacent to the school. Discovering that the cabin existed underneath layers of additions was quite exciting. Also, the writer who set the discovery in motion is working on a book about the Dotson Family and its connection to history.

ReplyDeleteI actually grew up in this home. I always thought the history behind it was going to be exciting, just not to the extent it was. We found many artifacts on the farm, from cannon balls to old coins. I’m so happy it will be restored to its former glory.

ReplyDelete