These images, pinned to the top of this blog, are shamelessly shared via-social media on personal pages, history blogs, and even the Smithsonian. The two photos side-by-side, one of a young girl

donned in a plaid dress and the other of a stoic woman with her hair pulled

simply back, have been timelessly interpreted to be “the richest Black girl in

America,” Sarah Rector - the very same Sarah Rector who lived out the majority

of her interesting life in Kansas City.

I have some important news to share with all of America.

I, too, fell victim to the forgery of these photos. Around Black History Month, I always see several posts about her story, complete with

these photographs of an unknown girl and a young woman. I mean, if credible sources are using the images,

they must be her... But they aren’t.

Just over a century ago, headlines spilled across America

and the world and are misrepresentations of what really happened to Sarah

Rector, her money and her family. The most important part lost in this saga is the

simple fact that her family got lost within the tabloids- tabloids worldwide

that painted a picture of a poor little black girl from Oklahoma who slept on

a dirt floor, struck it rich, was taken advantage of, and lived frivolously.

Some of these statements are partially true, but the true

story of Sarah should be told through her family. It was, in fact, her family

that was there for her through thick and thin.

How did I get this information? How do I know for

certain those images aren’t Sarah Rector?

|

| The Rector women who made this research & writing possible. L-R: Donna Thompkins, Deborah Brown, Rosina Graves, and Diann Brown. They are the daughters of Rosa Rector, Sarah's sister |

Families are the ones who hold the memories and records that

make up our collective history.

I always try to preface that history should be told in

stories, and those stories aren’t laced into the words of traditional history

books or told in timelines. You won’t likely find the real stories on the

Internet, and the good stuff is definitely not on Wikipedia. You learn the

truth behind the headlines by talking with people - with families- sitting down

with those that have collected the records, hold hundreds of photographs of

their own family, and can laugh as well as reflect on the past. I was lucky

that a line of the Rectors - Sarah’s nieces- were willing to talk to me and

share their story.

Let me tell you: Sarah's nieces are amazing, strong women.

| L-R Debbie, Diane (the author of this blog) and Donna |

I am blessed to be able to share their true legacy with the world.

*****

Sarah Rector, touted to be the “richest Black girl in

America” in 1913 when she was just 11 years-old, holds more than just

wealth in finances. To tell this story the right way- in order to paint the

picture of the “richest Black girl in America” – we have to understand the

circumstances surrounding Sarah Rector’s ancestry and the family that raised

her.

|

| Chief Opothle Yahola (1778-1863) |

The chief of the tribe, an Alabama-born man named Opothle Yohola (1778-1863) was one of these leaders who enslaved people. When he moved to Indian Territory, he settled on a 2,000-acre plantation near the Deep Fork River. One of his people in bondage was none other than a woman named Mollie, and Mollie would marry a man who was once held in slavery by Reilly Grayson. His name was Benjamin McQueen.

Chief Opothle Yohola may have owned chattel, but he wasn’t

willing to sacrifice it all and side with the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Even as most of the Creeks opted to follow the rebels, Opothle Yohola stayed

neutral during the early onset of the war. Due to the encroaching Confederate

troops, many Creeks fled into Kansas and joined the First Indian Home Guard.

Sarah’s maternal grandfather, York Jackson, served alongside Creek Indians as a

private. His father, Jack McGilbra (1821-1891) was enslaved by the Creeks.

Names in this family’s history can be complicated, so

bear with me. York had taken the surname “Jackson” in honor of being,

literally, "Jack’s son."

An enslaved woman held by Opothle Yohola named Mollie married

Benjamin McQueen and had a son named Jack Benjamin (another example of a

freedman choosing his father’s first name instead of a slave master’s surname).

Jack Benjamin left Indian Territory long enough to enlist in Lawrence, Kan. In

November 1863, he joined the Union Army as a private in the 83rd

Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops.

Even after these two men once in bondage left the service, they returned back to Indian Territory to rejoin

their family and friends.

Even after these two men once in bondage left the service, they returned back to Indian Territory to rejoin

their family and friends.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the Five Civilized

Tribes included 10,000 enslaved men, women and children - and they weren't freed just yet.

Jack Benjamin (cir. 1838-1915), for some reason, changed his

name to John Rector and married Bettie Corbner (b. 1846). York McGilbra Jackson

married Amy Manuel (1846-1936).

Shockingly, even though the Civil War abolished slavery across the nation, that didn’t include Indian Territory. In 1866, a treaty forced Native Americans to abolish slavery and allowed Creeks and these slaves (freedmen) to become United States citizens.

Shockingly, even though the Civil War abolished slavery across the nation, that didn’t include Indian Territory. In 1866, a treaty forced Native Americans to abolish slavery and allowed Creeks and these slaves (freedmen) to become United States citizens.

Freedmen such as Benjamin and Mollie McQueen, Jack Benjamin

(John Rector), Bettie Corbner Rector, York Jackson (McGilbra), and Amy McGilbra

were all freedmen born into slavery and eligible for land allotments according

to the treaty. At this time in history, Indian Territory had been reduced to 20

million acres. Each freedman was given 160 acres of land, and the Creek

Freedmen chose to settle together and form their own town.

|

| Amy Manuel McGilbra (1846-1936) with Joe and Rose Rector's daughter, Rosa (1913-1992) Photo courtesy of the Rector descendants |

Sitting eight miles west of Muskogee, Taft today is one of

only thirteen all-Black towns still in existence in Oklahoma. At the time, it

was one of fifty settlements founded by freedmen.

John Rector and his wife, Bettie had a son named Joseph (b.

1878), and York McGilbra Jackson and his wife, Amy had a daughter named Rose (b.

1886). In an all-Black community concentrated on farming cotton and corn, it is

certain that these two families knew one another for quite a long time.

Just because they were allotted 160 acres apiece didn't mean they were resistant to poverty; it was quite the opposite.

To think that these families, mostly illiterate and lacking

formal education at the time, were able to build the bustling early 20th

century town of Taft is inspiring. According to the Oklahoma Historical

Society, Taft had two newspapers, three general stores, a

brickyard, drugstore, a soda pop factory, a livery stable, a gristmill, two

hotels, a restaurant, a bank and a funeral home- all before 1910.

Joe and Rose likely attended church, dances and social gatherings together for many

years before they decided to take the plunge. First came their daughter,

Rebecca (called Becky) in 1901 and Sarah followed on March 3, 1902. By 1906, a

boy named Joe Jr. joined the growing family.

They didn’t have much; the dusty streets of Taft were the center of their entire social existence. In 1907, the town’s population

clocked in at a whopping 250 with most of the community traveling to it

from their Indian allotment lands outside of town.

The growing Rector family resided in a two-room cabin

situated on Rose’s allotment of land. Yes, two rooms are tight- but it’s likely

to have been the condition of most, if not all, the freedmen that lived in the

area around Taft.

Allotments were about to run out, and the Rector’s knew it

was time to get in line for their children. The cutoff date of March 1906 only

allowed their three oldest children, Becky, Sarah and Joe to get a piece of the

lands even though they welcomed a daughter, Lou Alice in 1907.

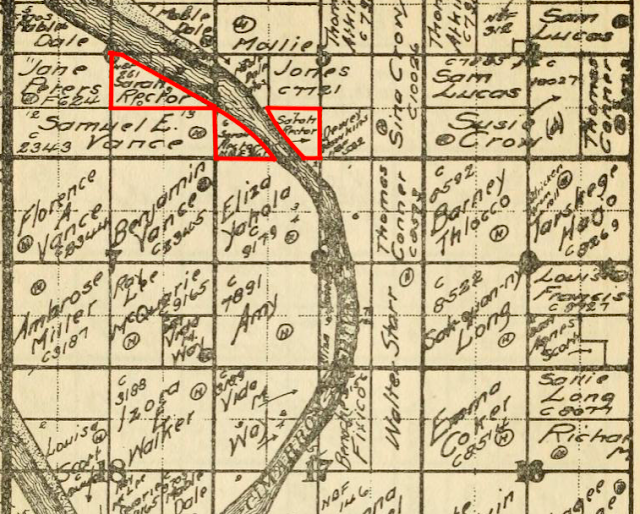

|

| Sarah Rector's land allotments on the Cimarron River is highlighted on "Hastain's Township Plats of the Creek Nation," 1910. |

Nor did anyone ever in a million years think that a freedman would become a millionaire.

To own land- even land with the rockiest, driest soil-

requires taxation. Taxes, people. Taxes always seem to play into the Rectors

rise and demise.

|

| "Home of the Creek Freedmen," Oklahoma Territory, cir. 1900 Image courtesy fo the Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior |

But, was that enough? Was that $1700 going to support a

family that had now grown to 7 mouths to feed? It was certainly a ton of money to a family

living in a two-room cabin.

There was soon a buzz within the community of

Taft. Oil- the black gold of America- had been frequently discovered in farms sprinkled across Oklahoma. It seemed that the richest soil in the area didn’t

necessarily hold the high dollars below ground… it could be anywhere.

…Especially on untouched rocky, grimy lands allotted to

freedmen.

By 1911, Joe was desperately trying to rid himself of

Sarah’s land. The new promotion of possibly leasing land to these greedy

oil-diggers presented a new opportunity for the Rector’s presumably useless

land so many miles away from them. Joe ended up quite satisfied when he was

able to lease Sarah’s land to an oil company out of Pennsylvania. He received a bonus of $160.

They still didn’t strike oil. The lease ran out and nothing

happened. But things had happened on other freedman lands, and the results led to nothing positive.

Money can, indeed, create problems.

|

| Faculty at Taft School. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society |

Oil had been discovered on other Indian allotment lands

given to children. In the same year, Harold Sells, 13, and his sister, Castella, 10, struck the big time when oil was discovered on what was assumed to

be useless land. In the middle of the night, dynamite was placed under their

house in Taft where the two children were sleeping. The house erupted into pieces.

Harold was killed instantly. His little sister was trapped under burning timbers

and was not as lucky.

These kids were murdered for an estate valued at just over $50,000.

These kids were murdered for an estate valued at just over $50,000.

Several men, both Black and white, were implicated in the

crime, including Jim Manuel, likely a distant relative of the Rectors. The

surname “Manuel” was in fact Rose’s mother’s maiden name.

More on this connection soon.

|

| Headline in the Muskogee Daily Phoenix April 26, 1915 |

A year later, another lease for Sarah’s land came through-

but for only $80. At this same time, a “gusher” had been located about five

miles south of Sarah’s land. That’s when karma kicked in.

In March, when Sarah was simply attending school in nearby

Taft, oil driller B.B. Jones assembled the necessary equipment to

check out Sarah Rector’s land near the Cimarron River. Any oil produced would

give a 12.5% royalty to the land owner.

In late August 1913, B.B. Jones produced a “gusher” on the

land leased from Sarah’s allotment. Quickly, this oil gusher produced 2,500

barrels of oil per day. Sarah’s cut- per day- was $300.

That was a hell of a lot of money.

By this point, Sarah was the second oldest of six children,

her parents welcoming Alfred, Lillie and little Rosie by 1913.

New siblings weren’t the only thing new in Joe and Rose’s

life- they had a daughter who was transformed as a little lack girl from Taft into a millionaire headline overnight.

Headlines such as “Girl’s 112,000 a Year,” “Negro Girl Will

Pay Largest Tax,” and “Negro Girl Rich From Oil- Has Income of $475 Daily –

More Soon” sensationalized the story of a small girl and her family’s reality. When

this gusher was started by the work of B.B. Jones on Sarah’s land, the family

still lived frugally in their little cabin.

| Photo courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society |

This may seem strange to us now, but it was commonplace in

this era to have white legal guardians taking a cut of the royalties in order

to supposedly “protect” an estate. Guardians got on average of two to six percent

of the profits, and in the case of T.J. Porter, he got less than two percent.

When I asked the Rector descendants on their personal

feelings about Porter, they described him as being a fair man.

Regardless, he was in control of all bankrolls from Sarah’s newfound

wealth.

In November 1913, Joe was receiving $50 per month for

Sarah’s care, which was a ton of money in those days.

They even eventually had a seven-passenger Cadillac, a big

upgrade from a horse “too old to work.”

It wasn’t long before the accusations came pouring in from

outsiders.

|

| The headline on November 29, 1913 in the Chicago Defender |

Due to her newfound wealth, publications across America

wrote of marriage proposals, especially

those that came from four white men from Germany. “Evidently the color of an

heiress does not matter if the color of her gold is genuine,” wrote Edward

Curd, Sarah’s attorney. He also concluded that the men that wrote her were

“fine looking chaps.”

By October 1913, 11-year-old Sarah Rector received $11,567

in royalties from the gusher.

|

| Booker T. Washington |

These are all lies.

The headlines didn’t shake the foundation of this family, and

T.J. Porter had to answer to so many of these accusations. In December 1913, Sarah got a

phonograph, a piano, and they built a new five-room home for her and her

family.

Between the marriage proposals, the mistreatment of funds

and the idea that Sarah was not being furthered academically became a target of

the public. The NAACP got involved due

to the continuous reports from the Chicago

Defender. W.E.B. DuBois personally wrote the judge overseeing her

allotments and asked that they ensure that little Sarah- not her siblings-

receive the best education offered.

|

| November 28, 1918 addition of the Chicago Defender created a stir with the NAACP |

That would be a “no.”

It was reported that Sarah had still never slept in a bed

(but on a pallet) and she was still living in a “poor house” on her mother’s

land.

The truth was that the family was in what we could call in a

moderate condition; they were not in dire straits.

Even when the children were still attending school in Taft,

the financial problems continued. By Spring 1914, Sarah’s allotments had given

the family just over $55,000 in royalties. Just a short time later, the

pressure from the NAACP and Black leaders across America who had read her story

had Sarah leaving home and heading back to where, ironically, the story began:

Alabama. Sarah was to attend the Tuskegee Institute’s elementary school called

the Children’s Home, but she wasn’t going to do it alone. Her mother insisted

that older sister Becky go along to ensure her younger sister was in good hands.

Even after Sarah and Becky left for Alabama for better

schooling, the newspapers reported that they were living in a tent.

After one year, the girls went to Fisk University’s boarding

school before rejoining the Rector family for Christmas break in 1916. No

evidence exists that the girls returned to school in Alabama, and it's likely the family moved

shortly thereafter to Kansas City.

Most of Sarah’s money was held up in investments across the

community and in bonds. By the time she left for school, T.J. Porter had

arranged for her to buy over 2,000 acres of land that he then leased for income. One of her

bigger investments was in a two-story building in Muskogee at 213-223 S. 2nd

St. that included the Busy Bee Café. The top floor was renovated and became the

Busy Bee Hotel.

Sarah’s family still remembers hearing stories of the Busy

Bee Café.

By the time Sarah was 18, she was worth well over one

million dollars. Likely in order to escape scrutiny and not wanting to be the

target of some greedy party’s act, Sarah’s family secretly slipped away and

moved north to Kansas City by 1917. By 1918, Joe Rector is listed as living at

1218 Euclid in the heart of what was becoming a booming African American

community. The family appears to have lived here for at least three years.

As fate would have it, the Rector family would further

reside in Kansas City and visit their beloved home of Taft when they could.

|

| The caption suggests Sarah Rector bought the home, but her mother, Rose did. Published in the Kansas City Sun, September 11, 1920 |

The Rectors settled into the east side of Kansas City in the home Rose

bought at 2000 E. 12th, now oftentimes referred to as the Rector

Mansion.

Even as the Rectors relocated to Kansas City, there were

transactions and business to attend in Oklahoma. By 1918, there were 50 oil

wells on Sarah’s land, and a new contract with a Kansas company resulted in a

$300,000 signing bonus.

In 1918.

|

| Mama Rose Rector posing inside the Rector Mansion in the 1920s Photo courtesy of the Rector descendants |

They just didn’t think that mansion was lovely, but they set

out to buy the block. By 1920, the Rector family, including 18-year-old Sarah,

were all living in a home previously occupied by Henry S. Ferguson, president

of the U.S. Water & Steam Supply Company. He had lived in the home for over 17 years.

The house, known today (inaccurately) as the Sarah Rector

Mansion or House, was actually purchased by Rose Rector for $20,000 after they

leased the home for several months. At the time the house was purchased, it was

said Sarah was worth one million. The house was known as “Sunset Manor."

Quickly, the entire frontage of 12th St. from Euclid to Garfield was bought with Rector money. Just as had been done while Sarah was under guardianship of T.J. Porter, investing money and leasing land was part of the Rector portfolio.

Not every segment of the Rector history is rosy. Even before the family's wealth, Joe had his run-ins with the law. Joe’s reputation may have made Rose’s parents a bit nervous when they decided to get married. In 1898, Joe was stabbed twice in Twine, once in the right shoulder and once in the left chest. Although it was originally thought he would die from his injuries, he survived.

In 1916, Joe was involved in a lawsuit with his mother over falsified

deeds, and in 1920, there was a "disagreement" after a game of cards in Taft that had a

gun pulled on him. Luckily, even though the gunman shot at him twice, Joe was

unharmed.

Even Joe’s own brother Fred tried to get in on the money management of Sarah’s lands. That alone tells you how contentious, and how important, it was that the family move away.

The Rector family came to Kansas City for a new life and to

obviously avoid the misfortunes that overtook other freedman families over

money.

In 1922, the Rectors had a really big year-both good and bad.

Sarah wanted nothing more than to have control over her own money after years of guardianship, and even though she had turned 18 in 1920, people still wanted their hands in the pot.

This was good and bad. At this same time, Joe Rector allegedly received a call from an old acquaintance named Jim Manuel.

Not every segment of the Rector history is rosy. Even before the family's wealth, Joe had his run-ins with the law. Joe’s reputation may have made Rose’s parents a bit nervous when they decided to get married. In 1898, Joe was stabbed twice in Twine, once in the right shoulder and once in the left chest. Although it was originally thought he would die from his injuries, he survived.

Even Joe’s own brother Fred tried to get in on the money management of Sarah’s lands. That alone tells you how contentious, and how important, it was that the family move away.

| The Rector Mansion at 2000 E. 12th St. |

In 1922, the Rectors had a really big year-both good and bad.

Sarah wanted nothing more than to have control over her own money after years of guardianship, and even though she had turned 18 in 1920, people still wanted their hands in the pot.

This was good and bad. At this same time, Joe Rector allegedly received a call from an old acquaintance named Jim Manuel.

Does that last name sound familiar?

Remember those two little children killed by dynamite after their allotments ended up with oil reserves on them?

Jim Manuel had allegedly been involved in the dynamite explosion in

Taft that killed two children with oil allotments. Albeit, he was not

one of the two men who were given life in prison.

He also had a rap sheet that makes Joe look like a saint.

Jim Manuel had a list of crimes in Oklahoma that reached

back to 1895; he was labeled as a “notorious negro” arrested for forgery of

five checks, deeds, and for stealing a horse and buggy. He was labeled “a

dangerous hombre” when he tried to take a gun into a jail so he could shoot

officers.

In 1913, he was said to have a set of gold teeth that would

disguise his identity and a warrant in almost every county in Oklahoma. He was

“charged with enough misdemeanors to send him to the penitentiary for life.”

Instead, they put him in for ten years.

That didn’t last.

|

| Headline featuring Jim Manuel's arrest in the Muskogee Daily Phoenix, Oct. 19. 1913 |

Jim Manuel, about 40 years old, was always up to no good.

Maybe Joe didn’t see it for some reason, even though Jim was responsible for

defrauding his own sister in Taft years before.

As an inmate in the Missouri State Penitentiary, Jim

allegedly contacted a Mexican lawyer he knew from prior “endeavors.” The lawyer

then contacted the warden and claimed that Jim had lands gushing with oil worth

millions of dollars. Jim was described as “60 years old, skinny as a rail, bald

headed and without a natural tooth in his head.”

With the pressure of the warden, Jim Manuel was able to

allegedly arrange a meeting at the Rector Mansion with a prison guard

in tow. He pleaded with Joe, stating that he couldn’t get to the land worth so

much money in oil without his help and promised to give him half of the

money earned.

Rose Rector definitely didn’t like the scenario, but as her

descendants told me, “Mama Rose” was always “including Joe in financial

decisions.” Rose was a hard worker as a laundress prior to the financial

windfall, and she knew hard work in her day. It was said in many

records that she was “stingy.”

|

| Original telegram sent to Mama Rose Rector July 10, 1922 mentioning Joe Rector's body being transported to Muskogee, Okla. Courtesy of the Rector descendants |

In order for Jim Manuel to show Joe Rector where the alleged

$40,000,000 oil gusher was in Mexico, he had to be free. In turn, Joe was able

to talk his wife (allegedly) into paying his $8,000 bond plus $2,000 in

expenses to go to Tampico, Mexico and get his half.

|

| Headline in the Muskogee-Times Democrat, July 11, 1922 |

Maybe? That could be true, but it is also a possibility that

what the papers reported were embarrassing for the rich Rector family. The

truth lies likely somewhere in between these stories.

While on their adventure, Jim Manuel and Joe Rector

arrived in Mexico on Joe’s dollar and all the money evaporated while trying to

target this land in Tampico. Not too long after arriving, Jim Manuel disappeared into

the sunset. All records indicate he never, under his legal name, surfaced in

his homeland.

This left Joe all alone, broke, and with the heartache of

telling Rose what happened. The newspapers reported with much sensation that he

was desperate and finally wired his beloved wife at 2000 E. 12th for

the money to get home. Defeated, he “sobbed all the way” to Dallas where “his

sorrow killed him” as he traveled by train on his way back to Kansas City.

What?

Joe’s death record tells different story.

It shows that from July 7 to July 8, Joe was seen by a doctor at Baylor

Hospital in Dallas. His cause of death looks like “trauma” and the underlying

cause was kidney disease.

It was known that Joe had prior operations for health

reasons.

Regardless, the newspapers registered this unfortunate death

as being the fault of Jim Manuel and his scheme for some of the Rector money.

|

| Sarah Rector at her home in Wyandotte Co. |

Several stories were shared about the family’s time in the

Rector mansion. In the back of the stately home was a two-story carriage house

with servant’s quarters on the second floor. It should be no surprise that the

family had hired help in the Roaring Twenties, where less than a mile down the road was the booming 18th and Vine district - the hub of African American social activity.

Shortly after the death of Joe, Sarah married Kenneth Campbell when she was 20 years-old and her sister, Becky married as well. Cars and clothes seemed to be the favorites with the Rector women. A chauffeur was tasked with driving a series of expensive vehicles, including a Rolls Royce. When Rosa, Sarah’s little sister (b. 1913) was forced to go to school, the cries would echo throughout the Rector home.

It became a routine for her to be dressed while still

sleeping, put inside the Rolls Royce limo while she still slept, and the

chauffeur would struggle to get her out of the car and "get her butt into school.”

|

| A 1925 window display at Kline's at 11th and Main shows the fashionable items available along Petticoat Lane. Courtesy Missouri Valley Special Collections, KCPL |

$2,000 worth of silk underwear “and other silken wearing

apparel” valued at another $500 was stolen from a car outside as the vendor was

showing the ladies his new line of silks, trying to make a sale.

The ladies loved finer clothing, but being African American,

they were not allowed to shop alongside white patrons in stores along Petticoat

Lane. Many stores, including Emery, Bird, Thayer &

Co. (EBT) would shut their doors and allow the Rector women to shop freely.

Spending freely at the most fashionable stores was

commonplace for the Rectors in the 1920s. In 1926, Mama Rose must have been a

bit embarrassed when the exclusive Vogue Shop at the Hotel Muehlebach, which

featured “unusual style and exquisite designing” claimed she wrote a bad check

for $388.50.

|

| Kenneth Campbell and Sarah Rector Campbell appeared in the Kansas City Call shortly after their marriage |

Sarah’s husband, Kenneth Campbell focused on real estate

development and his Hupmobile car dealership at 18th and Vine. Sarah and her

mother, Rose were known for their fancy vehicles they raced around town in. In

fact, both women appeared to have a bit of a lead foot. Several speeding

tickets were issued to both of them- especially to Sarah.

When she was pulled over in her shiny green and black

Cadillac, Sarah would cockily turn to the officer and say, “Don’t you know who

I am?!”

Sarah had three children, Kenneth (b. 1925), Leonard (b.

1926) and Clarence (b. 1929) before her marriage- and her finances- fell apart.

|

| Sarah getting into her fashionable car, cir. 1950s. |

It was around this time that the

taxes on the Rector mansion came due. Taxes always seemed to be their downfall.

The home was sold to the Adkins Funeral Home.

Sarah and her older sister, Becky divorced their husbands

and moved to much smaller homes on the east side. In 1930, Sarah was living

with her sister and her maternal grandmother at 2440 Brooklyn. In 1934, Sarah

married William Crawford, the owner of Dick’s Down Home Cook Shop at 1521 E. 18th

St. It was a favorite hangout of the Kansas City Monarchs baseball team.

To be clear, Sarah still had quite a bit of money, but she

didn’t have the ability to throw money around like she had once. Her siblings

all took on jobs- her mother even for a time went back to working as a maid.

Sarah was known for her extravagant parties that are

oftentimes referred to as being in the Rector Mansion on 12th St. where

she entertained musicians such as Count Basie and Duke Ellington. There is no

doubt that some parties would have occurred in this beautiful home, but the

real parties happened, according to her family, when she moved to her home on

Lockridge on the east side of Kansas City.

| "Dick's Down Home Cook Shop" at 1521 E. 18th St. Image courtesy of Tonya Bolden |

That farm became the

gathering place for the family to remove themselves from the heart of Kansas

City and likely reminded the Rectors of the simpler life once lived in Taft,

Okla. Sarah was quiet and private; her easygoing nature could be witnessed

in those visits to the farm.

Sarah’s nieces spent many-a-summer visiting the farm in Wyandotte

Co. and visiting family down in Taft. One of Sarah’s dear friends from

childhood nicknamed “Big Momma” would race around the dusty landscape chasing

chickens- chickens running around without heads.

A few hours later, dinner of fried chicken was hot and on

the table. Needless to say, the children would say they weren’t hungry anymore.

|

| (L-R) Jeannie, Roy's wife, Mama Rose and Rosa |

The matriarch of the Rector family, Mama Rose, passed away

in 1957 and is buried in Blackjack Cemetery next to her husband and near

generations of freedmen trailblazers that led to the unique story of the Rector

legacy. Just over 10 years later, Sarah passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage

on July 22, 1967. Ironically, her body was brought to C.K. Kerford Funeral Home.

Her last stop in Kansas City was none other than the old Rector Mansion at 2000

E. 12th St. where she and her family had once lived a life of luxury.

Her

final resting place in the ground was back where the story began- back in

Taft, Oklahoma in that little peaceful parcel of land known as Blackjack Cemetery.

Today, there are many rumors that circulate around the

Rectors, and the reason for this began in the headlines that blasted across the

nation and world. The lies began then, and unfortunately, many of those lies

are still circulated as being the truth. Sarah wasn’t deserted by her parents;

she wasn’t left in the care of a white guardian. Her family loved and supported

her when they lived in a small two-room cabin on Mama Rose’s allotment, and

they loved and supported her when she struck it rich.

The family didn’t leave Kansas City as some have reported;

five generations of Rector descendants still call this place home. They have

sat back quietly as the rumors about their family recirculate every so often,

as that false photo of Sarah is placed at the top of newspaper headlines and

social media posts.

They drive by the abandoned Rector Mansion, boarded up and

falling into disrepair, wishing that they could find a way to buy it back and

bring it to its former glory. They cringe when someone says, “That’s the Sarah

Rector mansion!” because the home was for all

of the Rectors and purchased by Mama Rose, the matriarch of the family.

It’s the Rector Mansion.

|

| A watercolor painting of the Rector Mansion by Pamela Morris (2019) made for the Rector descendants |

“We would like to see the house restored and have it become

a historic landmark and museum,” the Rector descendants told me around the

kitchen table covered with photos, records and family papers. “We have things

we would like to share with everyone.”

|

| Sarah Rector at her farm with one of her nieces |

This article was meant to rectify the Rectors, to give them

some peace of mind that their family’s story is, in fact, part of the history

of our nation. But if it’s to be told, it must be told in its entirety. This

was meant to tell you about their whole family- not just Sarah – as Sarah’s

story is interlaced with her grandparents, her parents and her five siblings.

Today, it’s kept alive by relentless Rector women set upon making sure their

story from now-on is told right.

I am honored- humbled- that I was the one chosen to right

some of the wrongs placed upon this family’s legacy and share this family’s

powerful place in the pages of history.

Photos in this blog were courtesy of the Rector-Brown-Graves family. Please see below for additional family photos!

*If you liked this story, you need to check out my podcast, Kansas City: 2 States, 1 Story- It's FREE! Along with radio personality Bob Fescoe, we discuss local history in a fun, exciting way! To learn more about it, click here! If you enjoyed this story, please considering liking my facebook page, The New Santa Fe Trailer so you can read more of the stories I publish!

Recommended Reading:

Searching Sarah Rector: The Richest Black Girl in America by Tonya Bolden.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann

|

| Mama Rose (1886-1957) on the farm |

|

| Becky (1901-1968) and Rosa (1913-1992). Rosa's daughters supplied the information for this writing. |

|

| Lou (1907-1957) |

|

| Alfred (1909-1972) |

|

| Roy (1918-1991) |

|

| Arthur (1915-1989) |