Michael Heim, with his large belly and hopeful eyes, walked

up to the site that was once the Kansas City Driving Club’s headquarters and

quickly threw out $46,000 for land at 46th and The Paseo. This would

be the new location of Kansas City’s Coney Island – the pleasure palace that

had pumped the Heim beer directly to their thirsty patrons from their East

Bottom’s brewery.

|

| Heim Brewery in the East Bottoms with Electric Park in the background |

The future of the city was slowly shifting to the south, and

investors were buying up land near parkways and boulevards that had access to

the streetcar system. At the end of the summer season in 1906, Michael Heim and

his brothers J.J. and Ferd felt the need to uproot their successful Electric

Park and push it south, too.

The old Electric Park had covered just shy of ten acres, and

by moving to the southern edge of the city, the park tripled in size. Their

last season in the East Bottoms attracted 900,000 visitors, so moving was

certainly a risk.

|

| Ad for the second Electric Park from the Kansas City Star, 1907 |

Before opening for the 1907 summer season, Michael Heim,

working as foreman, had 325 carpenters, 75 laborers and 30 painters working

long days to reassemble the park at its new location while also adding to their

attraction list.

The “Scenic Railway” would be new and span one mile long

from 60 feet in the air. Its width of 185 feet caused the new ride to require

additional rides to be within the center of the track. The “hair raising drops”

from high in the sky had Kansas Citians ready to see the new Electric Park

firsthand.

|

| Gardens designed by George Kessler beautified the grounds; the covered promenade can be seen to the left |

The new band pavilion would seat 10,000 people, said to be

more seating than was even offered at the Convention Hall. The German Village

was to have seating for 4,000 and the new lake freshly dug was 3 and a half

acres big.

Set to open May 19th, 1907, the new Electric Park

included a half mile covered and paved promenade that led patrons to concessions from the entrance. The promenade was said to have been

modeled after the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City. This was innovative for

the time, and Melville Stoltz, considered an authority on amusement parks

across the nation commented, “I wonder if Kansas City knows that this is an

amusement resort ten years ahead of [its time].”

|

| Patriotism was evident at Electric Park |

This new promenade ended at

two white towers covered with 10,000 electric lights each at the edge of their

new pool. Resting in the center was the famous electric fountain with live acts

in the center.

Flower beds 200 ft. x 150 ft. were designed by George

Kessler and included 62,000 plants and flowers. In addition to the “Scenic

Railway,” new additions included rowboats in the lagoon, a skating rink, a

giant swing, a shooting gallery, billiard room, penny amusement parlor,

Hooligan castle, an arcade, photograph gallery, dancing pavilion, and the “Norton

Slide” that had a series of long inclines 1,280 feet long.

The park was so large that three entrances were fashioned:

the main streetcar entrance at 47th and Lydia, a carriage,

automobile and pedestrian entrance at 46th and Lydia, and the Vine

Streetcar entrance at 45th and Woodland. Surrounding the entire

park, painted white, were 324 American flags varying in size from two to twelve

feet waving in the wind amidst 100,000 electric lights.

The park was so large that three entrances were fashioned:

the main streetcar entrance at 47th and Lydia, a carriage,

automobile and pedestrian entrance at 46th and Lydia, and the Vine

Streetcar entrance at 45th and Woodland. Surrounding the entire

park, painted white, were 324 American flags varying in size from two to twelve

feet waving in the wind amidst 100,000 electric lights.

Frankly, the only “old” thing about the new park was the 10

cent entrance fee. Opening day was an incredible success with 53,000 visitors

crowding the park- equal to how many people visit Disney World in one day

today.

|

| A young Walt Disney |

If you’ve ever waited in line at Disney World, you know that’s

a lot of people. And to no surprise, Electric Park was host to Walt Disney when

he was a child living in Kansas City. It is said that the park influenced the

young man so much that he modeled his world-renowned amusement parks after what

he witnessed firsthand at Electric Park.

There was one thing missing on opening day that didn’t go

over well for the Heims.

The park was dry of Heim Beer.

When Electric Park moved, they expected that their

liquor license would move with them to their new location… even though they

knew the 12th Ward where the park was newly located was vehemently

opposed to granting anyone a saloon license. The police board of three made it

vividly clear they weren’t about to grant them a transfer of license. The Kansas

City Star seemed to hold their own opinion when they wrote May 2nd,

“Those who desire [liquor] are the ones who should not have it.”

Lame.

Many of these pre-prohibition party poopers protested in

Jefferson City against granting Heim’s Electric Park a license to sell their

booze. Heim responded by launching a petition and hiring lawyers to fight

the stall of their license transfer. By June, it was declared that the subject of

liquor at the park was a source of “political agitation.” In response, they published a letter in the Kansas City

Star. They declared that, at the old park where beer and wine was sold, “There

was never an arrest for drunkenness.” They asked, “Should we be denied the privilege

which others enjoy under the law?”

Unfortunately for thirsty patrons and for Heim’s pocketbook,

the letter and petitions did nothing to sway the police board. They took their

fight all the way to the Supreme Court after appealing to the Jackson Co. Circuit

Court. They denied Electric Park’s applications to advance their license

on their docket. The court predicted it would be two years before they’d get to

their case.

Unfortunately for thirsty patrons and for Heim’s pocketbook,

the letter and petitions did nothing to sway the police board. They took their

fight all the way to the Supreme Court after appealing to the Jackson Co. Circuit

Court. They denied Electric Park’s applications to advance their license

on their docket. The court predicted it would be two years before they’d get to

their case.

Even though the park would inevitably stay “dry,” the Heims

were raking in the dollars. In the off season, Michael would travel all over

the country to search for the newest and greatest amusement park finds.

Numerous headlines reading “No Beer at Electric Park!” were replaced with

exciting updates on what would be state-of-the-art for the coming season.

New in 1908 was “The Tickler,” an eight-person ride

featuring a circular washtub-shaped car. It was designed to release parkgoers

at the top and pivot them against padded poles as it descended to the bottom in

a zig-zig pattern. For four minutes, passengers would be whiplashed all the way

to the bottom.

Each year created additional challenges to stay current and

the best amusement park option in the city. Fairmount Park and Forest Park

tried to rival Electric Park with free admission and gimmicks such as balloon

launches.

Each year created additional challenges to stay current and

the best amusement park option in the city. Fairmount Park and Forest Park

tried to rival Electric Park with free admission and gimmicks such as balloon

launches.

No balloon launch was going to beat the crowds and

attractions at Electric Park.

Rides such as the “Spiral Coaster” were added in 1910 along with

an ostrich farm and a miniature railroad. The following year, the park

abandoned the boat rentals on their lake and focused on building a bathing

beach that would allow for 5,000 swimmers at once.

In fact, Michael Heim is credited for being the man who “made

swimming a fashionable and almost universal sport” in Kansas City.

|

| "The Bowls of Joy" drawing depicts the coaster that never got off the ground |

“The Ben Hur Racing Coaster” was added in 1913 and gave park

visitors yet another reason to cough up the money to ride on one of the largest

and fastest coasters in the nation. Another addition that year included “Bowls

of Joy,” a ride invented and financed by a Kansas City post office worker. $15,000

was wasted on the ride and created six months of mechanical problems for the

park. “Bowls of Joy” became known as “Bowls of Deferred Hope” due to its

failure.

Most of Electric Park’s additions were a success. By 1915,

the freshwater pool was extended to be 53x133 feet and ranged from three to

eight feet deep. It took 430,000 gallons of water to fill it, and the four and

a half acre lake took six million gallons of water. For each season, Electric

Park ordered over one and a half tons of swimsuits.

|

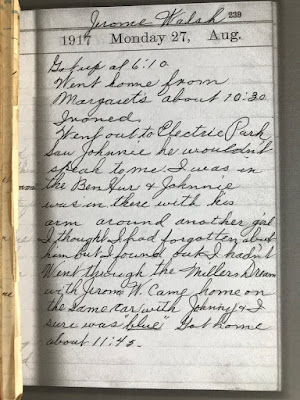

| My own great-grandmother, Jean Fetter (1900-1984) mentions Electric Park and riding the "Ben Hur" and "Millers Dream" in her diary entry from Aug. 27, 1917! |

“Alligator Joe,” a large attraction at the first Electric

Park, continued his alligator antics for several seasons at the new location. In

May 1915, five alligators two to three feet long escaped into Brush Creek.

Three were recovered within a few days, but two were still missing.

In late August, the two other alligators were found in the

Missouri River…

…in Jefferson City.

Constant updates to the park’s innovations made Electric

Park a draw for people all over the Midwest. The Heims heavily invested in new

attractions in order to stay relevant – they had new competition that included

silent movies and the ability to be mobile. The affordability of the automobile

had Kansas Citians taking “driving tours” in lieu of taking the streetcar to

their park.

In 1917, Electric Park featured the “Greyhound Ride” that

Michael Heim declared “is the highest and longest thriller in America.” Water

rides including “The Whirlpool” and “Millers Dream” kept them in competition.

Minus nine injuries on the “Ben Hur” caused when a car at

the end of the ride wouldn’t stop and an incident on the “Greyhound” where a

man dropped a lit cigar on the ride and caused the shavings under the

rollercoaster to catch fire, the park was miraculously free of major injuries.

|

| Electric Park at night |

The biggest crowd ever documented at Electric Park happened in

midst of World War I when former President Theodore Roosevelt came to speak

there on Sept. 24, 1917. 55,000 people piled into the park for one dollar, and

all the proceeds for admission were given to the Red Cross.

The influence of the World War could be seen and experienced

at Electric Park after its end. In 1919, “Hales Aerial Travels” and “Race

Through the Clouds” were additions, the latter supposedly the longest ride in

the world. The significance of the War also influenced ticket prices when the

war tax was issued. Electric Park finally raised their prices to 15 cents- 13

cents for admission and two cents for the war tax.

|

| "Alligator Boy" Henry Coppenger, Jr. taken in Florida in front of hundreds of people |

Perhaps because “Alligator Joe” had retired south to

Florida, Michael Heim grabbed “Alligator Boy” in 1919 to be another feature at

Electric Park. “Alligator Boy,” whose given name was Henry Coppenger, Jr., was

billed “the most interesting youth in America.” He swam in tanks of water with

34 alligators more than six feet in length.

One day, Michael Heim walked past Alligator Boy’s massive

display. He pointed to Alligator Boy, and without any warning, an alligator

attacked Heim and nicked his finger in the process. Although the injury wasn’t serious,

Heim was spotted the next day “wearing a bulky bandage” as he retold his

harrowing fight.

|

| Electric Park's 643 year-old alligator Courtesy of John Dawson |

Prohibition in 1920 put a dent in the Heim brother’s profits

as their main income was the Heim Brewery. When the tap ran dry across the

nation, they focused on their real estate holdings and their beloved Electric

Park.

The “Big Dipper” was added in 1922; passengers plunged

straight down 80 feet sixteen times in a row for over a mile. A new beach with

a “sea breeze” drew more patrons in 1923. They must have not noticed the fans

tucked into the two towers in order to create the gusts of wind on the

artificial coast.

Michael Heim, the brainchild of Electric Park from the

beginning, was tired. It’s as if a higher power was listening when on May 26th,

1925, a fire engulfed much of the park in flames.

Ironically, Electric Park was almost completely annihilated because

of its initial draw: electricity. The fire chief said a wire from a transformer

in front of “The Bug House” became overheated. When the wire broke, it fell on

an extremely flammable building. Damages were estimated at over $100,000.

|

| The fire damage from May 26, 1925- published in the Kansas City Star |

“One of these years, a May will come when Electric Park will

not open,” Michael Heim commented the next day. “Ultimately – possibly in a

year or so- it is planned to replace the amusement park with an apartment

development and a large shopping center.”

Mounting taxes complicated things; plus, a new park called

Fairyland had opened a few years’ earlier. They admitted that the success

of the 1925 season would make their final decision.

|

| The Electric Fountain with "living acts" in the center was moved to China after the park closed |

Profits were lower than anticipated, and the decision to

close Electric Park was reached. It was time to end of 25 years of

entertainment.

August 1925 was the final month for the Electric Park era. A

Mardi Gras celebration and a corn carnival were the final festivities that

closed a chapter for so many Kansas Citians. The park had been the site of countless

memories, laughs and thrills.

The famous electric fountain was shipped off to Guangzhou, China.

Its fate is not known.

The pool and dancing hall were all that remained of the park

until a fire in 1934 destroyed the final pieces of the pleasure palace.

The same month and year that the second Electric Park

closed, another chapter opened for the Heim family’s legacy. A dedication

ceremony at the original site of Electric Park in the East Bottoms was conducted

to introduce the city to a new public playground. Heim Park opened in 1925 as

another park closed for good.

|

| Heim Park in the East Bottoms, the original location of Electric Park. Courtesy of KC Parks |

But there is hope soon yet for revitalization of the

electrifying days that once stood next to Heim Brewery.

On August 28th, 2018, in the shadows of where

Electric Park once stood, Andy Rieger, co-founder of J. Rieger & Co.,

addressed a crowd that included most of the city council and Mayor Sly James. This

announcement will change the landscape of the East Bottoms and is being

spearheaded by J. Rieger & Co., a revitalized pre-prohibition distillery

that uses the Heim Brewery bottling plant as their headquarters today.

|

| A view of the future of Electric Park and J. Rieger & Co., housed in the historic Heim bottling plant Courtesy of J. Rieger & Co. |

Heim Brewery bottling plant was built in 1901 and is one of two surviving structures of Heim Brewery in Kansas City. With the addition of

the bottling plant, Heim was able to produce 125,000 bottles per day and at one point

was the largest pre-prohibition brewery west of St. Louis, Mo.

Andy is extremely thoughtful when it comes to preserving the

historical significance of J. Rieger & Co.’s headquarters. “I love how we

are going to keep the building looking as historic as possible. Historic buildings that are renovated to

remain historic, but updated in a cool way with a cool use are about as good as

it gets in my eyes,” Rieger commented.

|

| Andy Rieger, co-owner of J. Rieger & Co. is working hard to preserve history and revitalize Electric Park. Photo courtesy of J. Rieger & Co. |

Even though Electric Park went dark in the East Bottoms in

1906, it has been Andy Rieger’s goal to bring life back to the neighborhood and

rebrand it. Their current space of 15,000 square feet will expand to 60,000

square feet between two buildings. This expansion includes renovating their

distillery space and the historic Heim Brewery bottling house and adding daily

tours, a bar, lounge and cocktail spaces, event spaces for small and

large-scale events, a gift shop and a free interactive historic exhibit on the

main floor that will include the history of Heim Brewery, Electric Park and J.

Rieger & Co.

“All these things are the big focus of being able to

revitalize the name ‘Electric Park’ and what it once was,” Andy stated.

New sidewalks, streets, landscaping and a parking lot will

help transform the outside grounds. Rieger’s hope is to rebrand the ‘East

Bottoms’ name back to Electric Park. “We are really proud to be the ones

bringing back the entire nature of Electric Park,” Rieger commented. “We want

to bring that motto back to the neighborhood.”

The investment in what will be coined Electric Park includes

the city recognizing the past contributions of innovators such as Heim Brewery

and current contributions by J. Rieger & Co. Mayor Sly James stated, “This

investment is equivalent of the pioneer investments that were made in the West

Bottoms and in the Crossroads.”

|

| A view from the new entrance to J. Rieger & Co. facing southeast Courtesy of J. Rieger & Co. |

Taking a risk on a multi-million dollar investment in the

area isn’t something that just anyone would do. But just like the Heim brothers

in 1900, J. Rieger & Co. is willing to roll the dice and draw people down

to Electric Park to see what progress and advancement looks like firsthand.

Kansas City needs more

businesses like J. Rieger & Co. and more people like Andy Rieger. He is

completely devoted to the city he loves, and this love is apparent when you meet

him.

“All these projects started with somebody being willing to

make an investment in an area that people weren’t investing in,” Mayor Sly

James said.

By 2019, what was once referred to as the East Bottoms will

have a completely new face with the help of the history of Electric Park. J.

Rieger & Co. is proud to tell the story of the past and incorporate it into

their ideas for their own company’s future.

“History is our

brand,” Andy Rieger stated. “We are so lucky to be given this nearly limitless

basket of an authentic past.”

I hope you will #meetmeinelectricpark!

Check out their cool video below. :)

Check out their cool video below. :)

To stay up to date on all of my writing, search "The New Santa Fe Trailer" on Facebook and LIKE my page! :)